Halim Mama

A few weeks ago I received a call from my sister. It was Saturday night, past 8 p.m.

My senses immediately heightened and I knew something was wrong. Through muffled cries, she said, "Halim Mama died."

I shouted, "What?!” As I collected my thoughts, I turned off the oven mid-dinner planning and drove home, urging Susana to get Mom to take her anti-anxiety medication before sharing the news.

When I came through the door, Mom already knew, shaking from grief and in shock.

We were all in shock.

In a family of eight brothers and sisters, Halim Mama was the first to die.

He was the kindest, the tallest, and without a doubt the smartest.

Abdul Halim was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 1969. He was the third sibling born to a family of ten siblings, (later eight due to two SIDS-related deaths). He was the first son to be born and his spent his childhood, and the remainder of his life, listening more and

speaking less.

Though a man of few words depending on the crowd, Halim Mama had a voice that bellowed with joy. "Hoo Haa!," he'd say entering homes, dawats, and rooms alike.

When I began to learn how to write, my mom encouraged me to write him letters. Though I don't remember what I wrote in them, given that I was maybe five or six years old at the time, he surprised us with a one of those crumpled letters, carefully folded, when he visited New York in 2023. My heart was so full.

When he first visited New York City in 1997, he stayed for just one week after completing a scholarship program in Colorado. My father drove all of us in a small car to Atlantic City, the go-to vacation spot for most immigrant Bangladeshis in the late 1990s. We all walked to a casino and Susana and I ran ahead, excited to see the bright lights and slot machines. We were woefully unaware that these games were rigged and meant to empty the pockets of adults, not children.

Mom stayed behind in the lobby with me and my sister, and the elder males played the slots. My dad lost hundreds, but Halim Mama didn't spend a single dollar.

"Apa, eita shob faltu!," he laughed. Apa is the term used for elder siblings.

"Sister, these are all bogus."

He wasn't a fan of gambling, but witnessed first hand how my dad wasted money, despite the four of us living in a small, roach-infested one bedroom apartment.

While in New York, for the first time, Mama purchased a large black cowboy hat. When he wore it home, he opened the door of our long corridor in our tiny apartment in Jackson Heights. I didn't recognize him, and instead saw a tall, dark shadow with a massive head. I started to scream and cry in fear.

He emerged from the shadows and said, "Ma, eije ami, tumi bhoypaila?"

"My love, it's just me, you got scared?"

**********

As the extended family grew bigger, Halim Mama sent us photos of himself, Mum Mami, (his wife) and their baby girl. We looked in awe at the photos of him cooing over her after their brought her home from the hospital.

And the family continued to grow. First Neha, then Labib, then Rania, Jesse, Rudaba, Zuzar, Ereshva, Enan, Zubin, and Anahita in that midst.

Each child with a story, with a different set of siblings, and despite the distance or the circumstances, Halim Mama, or Boro Mama they endearingly called him, always maintained a relationship with each one of us.

My relationship had always been different. The eldest, immigrant daughter who was forced to grow up faster than most of the kids. Dealing with my father's abuse, infidelity, and gambling made me painfully aware that there was no room for me to make a mistake. I couldn't get a boyfriend, I couldn't get pregnant, I couldn't fail a single class.

I started to work when I was 14, tutoring middle-school aged kids. Halim Mama had done the same in his youth.

I found comfort our conversations about current events, politics, and life. He understood that kids were people. That we had feelings and understood more than we led on. And though I've found my voice now, as 30-something adult, I was that quiet kid for a long time.

Halim Mama's trips to NYC became more frequent after my mother's first open heart surgery.

In 2015, in 2016, in 2017, in 2018, in 2021, and finally in 2023. Like the rest of us, he always feared that we would lose Ma. None of us ever imagined that he would be the first to go.

He spent thousands upon thousands, traveling to and from Bangladesh to see my mom. His 6’3 figure crouched painfully into the plane seats, as he traveled over 24 hours, door to door, just to see us. He stayed for at least four weeks with every visit, and with each visit we grew closer.

This quiet person was seldom quiet in our home.

Our small, but cozy apartment served as a getaway from Dhaka. We no longer lived in our Jackson Heights, run down apartment, but a slightly bigger place in Rego Park. And this time - my father had moved out. (Well, forcibly removed but that's for another time.)

Halim Mama was able to be free with us, sharing his uncensored opinions on most happenings in Dhaka. We relished in his stories, and tagged along on his trips to Brooks Brothers, and Sephora where he stood confused, catering to the 2-paged lists of makeup requirements from the girls back home.

With every museum, he painstakingly took hours to read every single exhibit's cards and walk through every floor. He rarely completed a museum in one day.

When we went to the Intrepid together, he spent time speaking to each of the Veterans, asking them about their battles and specific details only a historian would remember.

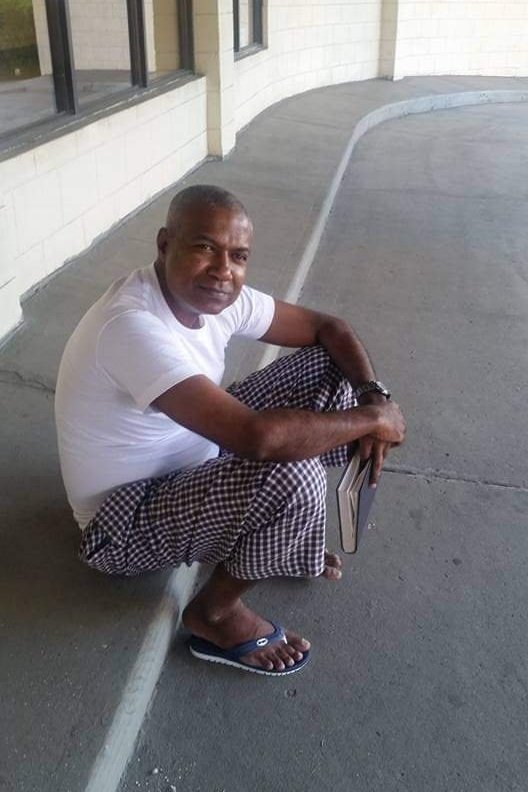

He had a horrific habit of smoking and smoked cigarettes every day. After my mom explained to him that he couldn't smoke in the bathroom anymore, he walked down to the lobby in the cold, many times in just his sweatshirt and lungi - a sarong wrap traditionally worn by men in South and South East Asia.

Every time I came home from work, there he was, in front of our Rego Park apartment building, smoking a cigarette, book in hand, legs crossed on the floor in his lungi. He giggled when I told him to wear pants and he tried to convince me that lungis were a better clothing choice for men.

He was the only one who could convince my mom to get into a small, Schooner boat off of South Street Seaport. We were the only People of Color on the boat, so when my mom started to shout "Allah," and I told her not the scare the other passengers, Halim Mama giggled and reminded her to remain calm.

Though he appreciated our conversations, he appreciated Susana's patience even more. She stayed by his side in every store, and waited for the stylish, yet meticulous mama to get through every aisle.

He loved tailored shirts with printed florals and bright colors. When I took him to Harlem, we walked into a Senegalese-owned shop, and he purchased a bright green shirt while discussing Senegal's rich history with the shop owner. He always reminded me of the importance of reading and constantly learning.

Halim Mama was a difficult person to shop for, because what do we gift to the Chief Auditor of a Bank? We relied on his likes and bought him personal gifts, like an etched wine stopper that said it was from “Your favorite nieces.”.

I remember filming his reaction, and he replied, “They film everything, don’t they?”

And I am so glad I do.

The most special gift he enjoyed was of an art piece of himself sparring with the great Muhammed Ali. He was a huge fan of “The Greatest,” and read many books on him.

But perhaps, our favorite memories together were going to The Bronx Zoo. He loved every exhibit, but especially lingered with the gorillas. He was always amazed at how human-like they were. He was thrilled to find out that my partner and I had chosen the Bronx Zoo as our wedding venue.

When it came time for the big day, none of my mom’s siblings came, even with the two-year notice.

Halim Mama broke the news that he needed to stay in Dhaka for his daughter’s final exams, for her last year. I was heartbroken, but understood. He told me in-person why he couldn’t come, leaving me with a parting gift towards the matrimony. I offered to pay for his round-trip flight, but he knew he needed to stay in Dhaka.

It was Halim Mama’s integrity and humility that made him so special.

He didn’t claim that he had a court case he had to tend to. He didn’t claim that his daughter’s bideshi boyfriend was the reason he couldn’t come. He never shouted at us and left our home in a fit of rage, while claiming to know everything about American appliances. He never claimed there was a work conflict. He never said he would come, and then leave a voice message that he couldn’t. He never judged my clothing choices. He never dated around in his 20s and pretended to be religious after 50.

He never said, “Aar ki bolbo?” “What can I say?”

He wasn’t a coward.

As the eldest brother, he ensured everyone was taken care of, even our cousins who need to live in the countryside, due to their father’s poor health. He made sure everyone had a piece.

To lose my father so suddenly was a pain I couldn’t explain. But to lose someone you wish were your father is a different kind of experience. Like losing a part of yourself all over again.

We both enjoyed reading. We both understood the importance of families. We understood the complexity of our loved ones. We both followed world events. And we both loved nature.

With his light gone from the world, I can only pray that he will be forever in our hearts.

As I kneeled in prayer during All Saints Day, I could only hope that he is with his parents, watching over us today. And that I can continue to emulate that kindness and grace he carried.

May he rest in peace. We love you, forever.